India’s decision to opt out of the “Will for Peace 2026” BRICS naval exercises in January 2026—despite holding the BRICS chair that same year—is not a tactical maneuver but a declaration of structural incompatibility. While Indian officials framed the absence as a technical clarification (the exercises were “not institutionalized” BRICS activities), the underlying logic reveals a more consequential reality: India faces a widening gap between BRICS’ increasingly anti-Western military alignment and India’s own strategic interests, democratic values, and economic integration with the West.

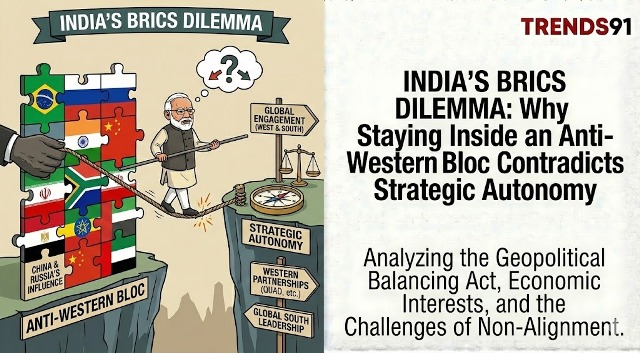

The question posed—why does India remain in a bloc when most of its interests are anti-BRICS—deserves a nuanced answer. India’s 2026 opt-out and its broader hedging strategy point toward a trajectory: India is not exiting BRICS imminently but is engineering a progressive downgrading of the bloc from a strategic partnership to a narrowly functional economic forum. This is strategic autonomy in practice—not choosing sides, but redefining the terms on which it engages with each side.

This analysis examines the structural contradictions that make full BRICS commitment untenable for India and identifies the probable evolutionary paths for India’s membership over the next 5-10 years. The verdict: India will remain nominally within BRICS but increasingly compartmentalize it, allowing India to hedge geopolitical bets while pivoting strategic priority toward the Quad, bilateral US partnership, and selective minilateral architectures that align with India’s core interests and values.

The 2026 Naval Exercise Snub—What It Actually Signals

The Exercise and the Absence

The “Will for Peace 2026” naval exercises conducted off Simon’s Town, South Africa, January 9-16, 2026, involved China (leading), Russia, Iran, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Indonesia, with Brazil attending as observer. India declined all participation—not even sending observer delegations. The absence was conspicuous for a country holding the BRICS chair that year.

India’s official response was procedurally precise. External Affairs Minister spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal clarified that the exercise was “entirely a South African initiative” and represented “not a regular or institutionalised BRICS activity.” India has not participated in previous such exercises, he noted, and does participate in IBSAMAR (India-Brazil-South Africa maritime exercises), which it considers the authentic BRICS naval forum.

The Technical Defense vs. The Strategic Reality:

The MEA’s distinction between “institutionalized” and “non-institutionalized” BRICS activities provided diplomatic cover, but the actual reasoning was more revealing. India’s decision reflected three explicit strategic constraints:

First: China’s Military Presence as a Red Line India views participation in exercises involving joint defense coordination with China as incompatible with its border security posture. Despite Prime Minister Modi’s meeting with Xi Jinping at the 2025 SCO summit and some diplomatic thaw, troop positions along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) remain at elevated deployment levels compared to pre-2020 baselines. India has consistently held that political trust must precede military cooperation. Participation in a China-led naval drill would be interpreted (both domestically and strategically) as normalizing defense ties absent a breakthrough on the LAC.

Second: The Militarization of BRICS as Mission Creep India’s External Affairs Minister had explicitly outlined his vision for India’s BRICS 2026 chair: Resilience, Innovation, Cooperation, and Sustainability—all developmental themes. The emergence of coordinated BRICS military exercises directly contradicted this framing and symbolized BRICS’ transformation from an economic development platform into a military alliance. India’s position was unambiguous: BRICS was “conceived for economic and development cooperation, not as a military alliance.”

Third: The Anti-Western Signaling Problem Participation in exercises explicitly designed to demonstrate operational interoperability among China, Russia, and Iran—three states in direct confrontation with the US—would send an unambiguous geopolitical message: India had chosen alignment with an anti-Western bloc. This calculus is what geopolitical analysts identified as the deepest motive. Harsh Pant of the Observer Research Foundation: “For New Delhi, opting out of the drills is about balancing ties with the US…BRICS is not something that can take [military transformation].”

The snub, therefore, was not a mistake or an oversight. It was a calibrated political decision: India demonstrating to both its Western partners and to BRICS that there are explicit limits to solidarity. India will not militarize its BRICS engagement. It will not commit to exercises that operationalize an anti-US coalition structure. These are India’s red lines.

BRICS’ Transformation—From Economic Club to Geopolitical Bloc

The Original BRICS Mandate (2009-2022)

When BRICS formed in 2009, it emerged as a voice for emerging economies seeking greater influence in global governance. The original mandate was developmental and institutional: reform the IMF and World Bank, create development finance alternatives, and assert the interests of the Global South in a Western-dominated international system. BRICS was not explicitly anti-American or anti-Western. It was reformist—seeking to reshape multilateral institutions rather than replace them.

The 2023-24 Expansion: Ideological Inflection Point

The decision to expand BRICS in 2023 to include Iran, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Ethiopia in 2024 marked a decisive pivot. These additions were not random; they represented a geopolitical statement.

Iran: An explicitly US-adversary state, sanctioned, facing internal collapse (which occurred in December 2025). Including Iran signaled BRICS’ willingness to embrace states in direct confrontation with Washington and to provide a counterweight to US sanctions.

Saudi Arabia and UAE: Both regional pivots that had normalized relations with Israel yet maintained strategic autonomy. Their inclusion offered BRICS access to oil markets and regional influence across the Gulf. However, both are nominally aligned with US security architecture.

Egypt and Ethiopia: Control Red Sea chokepoints and Horn of Africa geopolitics—regions of critical strategic importance. Their addition gave BRICS enhanced geographic reach and veto power over global maritime trade.

The Expansion’s Geopolitical Meaning: BRICS was no longer primarily an institution for economic cooperation. It was becoming a coalition of convenience—united less by shared developmental values than by a common resistance to US hegemony. The expansion explicitly targeted the West’s regional interests and demonstrated BRICS’ willingness to oppose US positions globally.

Evidence of BRICS’ Anti-Western Tilt: UNGA Voting Patterns

The clearest evidence of BRICS’ transformation comes from voting patterns at the UN General Assembly. These data reveal explicit bloc discipline directed against Western interests:

Russia-Ukraine Voting (2025):

All “old” BRICS members (Russia, China, India, South Africa, Brazil) abstained on Ukraine-related resolutions, maintaining formal neutrality. However, new BRICS members broke from this pattern: Egypt and Indonesia both voted “for” anti-Russian resolutions in March 2025, violating what had been a consistent practice of BRICS abstention since 2023.

More significantly, the pattern of unanimous BRICS opposition to pro-Western resolutions remained intact. Not a single BRICS member voted against Russia’s interests. The voting bloc operated with implicit discipline: unified resistance to Western positions, even if not unanimous support for Russian ones.

Bloc Cohesion Trend: Academic analysis confirms that BRICS countries vote together on critical issues far more than with Western blocs. Membership in BRICS, SCO, or G-77 is a “strong predictor” of voting alignment against US positions at UNGA. States in BRICS are 30-40% more likely to vote with China and Russia than with the US, a gap that has widened since 2015.

The Implication for India: BRICS increasingly functions as an explicitly anti-Western coalition. India’s participation implies endorsement of this alignment. Yet India’s core security interests—the China deterrent, the Quad partnership with the US, deepening US-India defense cooperation—are fundamentally predicated on resisting, not joining, an anti-Western coalition.

India’s Two Structural Mismatches with BRICS

1. Geopolitical Contradiction: China Is BRICS’ Core, India’s Primary Threat

The Fundamental Problem:

India joined BRICS partly to amplify its voice in Global South affairs and partly to hedge against Western dominance. Instead, BRICS has become increasingly China-dominated, transforming it from a platform for Indian influence into a platform for Chinese interests.

Evidence of China’s BRICS Dominance:

- China leads BRICS military exercises (Will for Peace 2026)

- China drives BRICS expansion strategy; all expansion decisions benefit Chinese geopolitical interests

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative is the principal development framework shaping BRICS+ countries

- China controls BRICS institutional discourse through intellectual output and media presence

- China dominates BRICS New Development Bank lending priorities and co-financing terms

Meanwhile, India’s Threat:

China is India’s core existential security challenge:

- Border Conflict: LAC tensions remain unresolved; Chinese forces maintain enhanced deployments; periodic military escalations (2017, 2020, 2022) have characterized China-India relations

- Encirclement Strategy: China’s BRI extends through Pakistan (CPEC), Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Central Asia—all vectors designed to constrain Indian influence and create strategic dependencies hostile to India

- Naval Expansion: Chinese submarine presence in the Indian Ocean has doubled since 2015; China is becoming India’s primary maritime competitor

- Technology Competition: China is positioned to dominate AI, semiconductors, and critical technologies that will define 21st-century power

- Taiwan Flashpoint: Chinese military modernization targeting Taiwan affects global trade, semiconductor supply chains, and regional stability

The Contradiction Crystallized:

India joined BRICS seeking to amplify its voice as a great power and hedge against Western dominance. Instead, India has found itself in an alliance where its greatest geopolitical adversary is the dominant voice. The logical response: compartmentalize BRICS, refuse to deepen military-security ties that would operationalize Chinese dominance, and invest strategic priority elsewhere.

India’s Malabar Exercises vs. BRICS Exercises:

The contrast is instructive. India participates eagerly in Malabar—the Quad naval exercise involving India, US, Japan, and Australia. These exercises are held annually, are increasingly complex and operationally integrated, and explicitly serve to enhance interoperability among democracies against Chinese hegemonic assertion in the Indo-Pacific. India participated in the November 2025 Malabar exercise in the northern Pacific near Guam, deploying an indigenously designed stealth guided-missile frigate and engaging in joint anti-submarine warfare drills, gunnery, and airborne maritime operations.

By contrast, India refuses to participate in BRICS exercises that China leads. The preference is unambiguous: India will militarize partnerships against China; it will not militarize partnerships with China.

2. Economic Integration Mismatch: India’s Future Is Western-Bound

The FDI Reality:

India’s foreign direct investment landscape tells a story of Western dominance, not BRICS interdependence.

FDI Inflows (FY 2024-25):

- Total FDI: $81.04 billion (14% year-on-year growth)

- Primary source: United States and Western countries dominate greenfield investments

- Critical sectors: Semiconductors (US-led), pharmaceutical (EU/US), IT (US), automotive (Japan/Germany)

- Strategic tech: US companies lead in AI, quantum computing, biotechnology investments

- Among ten largest greenfield projects globally in 2024, four were in semiconductor manufacturing—including one in India with US backing

Bilateral Trade Partnerships:

- US: $190+ billion bilateral trade; rapidly expanding strategic technology partnerships (COMPACT, iCET initiatives)

- EU: Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement negotiations; goods/services trade growing; FTA expected to boost FDI

- UK: Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement signed (January 2025); bilateral trade $56 billion; targeted to double by 2030

- Japan: Critical partner in semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, auto manufacturing

- ASEAN: India’s preferred Asian market (excluding Japan)

BRICS Trade Reality:

- China: India-China trade $137 billion annually, but massive deficit in China’s favor (India imports far more than it exports)

- Russia: Limited and constrained by sanctions; India buys Russian oil but sells little of value in return

- Brazil: Complementary trade but limited scale

- South Africa: Minimal bilateral trade

De-Dollarization Rhetoric vs. Economic Reality:

BRICS leaders regularly invoke “de-dollarization” and alternative payment systems (rupee-yuan settlement, BRICS payment network proposals, etc.). Yet India’s economy remains profoundly integrated with dollar-based global finance:

- US dollar dominates trade settlement (85%+ of India’s international transactions)

- India’s reserves are dollar-heavy

- India’s capital markets are dollar-dependent

- Rupee internationalization remains nascent; rupee settlement accounts <2% of India’s trade

The benefits of de-dollarization—if achieved—would accrue primarily to China (currency internationalization strengthens Chinese power) and hurt India (rupee lacks the depth to serve international functions). India gains little from de-dollarization and loses geopolitical flexibility from it.

Development Finance: NDB vs. World Bank:

The BRICS New Development Bank (established 2015) was intended as an alternative to the World Bank. By 2025, NDB had approved ~120 projects with total value ~$50-60 billion over a decade. In 2023-24 alone, NDB approved $2.06 billion across 10 projects, predominantly in Brazil and India.

This sounds substantial until compared to India’s actual infrastructure needs: India requires ~$1.5 trillion in annual infrastructure investment. NDB contributions represent <0.15% of annual infrastructure financing needs. India remains fundamentally dependent on World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and private capital markets—all Western-dominated.

The Economic Implication:

India’s prosperity and developmental trajectory depend on deep integration with Western markets, Western capital, Western technology, and Western supply chains. BRICS offers rhetorical alternatives (de-dollarization, alternative development finance) that deliver negligible economic benefit relative to India’s integration with the West. Economically, India has far more to gain from deepening Western ties than from strengthening BRICS integration.

Why India Stays (For Now) and Why It Won’t Stay Long

The Logic for Remaining Inside BRICS

Despite the structural mismatches, India maintains nominal BRICS membership and participates in most BRICS forums. Why? Several strategic rationales:

1. Voice in Global South Narratives

BRICS commands an outsized platform in Global South discourse. It represents 36% of global GDP, 46% of world population. By remaining inside, India shapes Global South narratives around climate finance, technology access, development equity, and institutional reform. Exit would cede this platform entirely to China-Russia, allowing them to claim monopoly on Global South representation.

2. Hedging and Leverage Extraction

By maintaining membership, India preserves optionality. India can threaten to tilt toward BRICS if the West ignores Indian interests, and threaten to tilt toward the West if BRICS moves too far toward militarization or explicit anti-Western declaration. This hedging posture extracts concessions from both sides.

Evidence: Trump administration’s tariff threats against India (2025) were partially offset by India’s ability to signal potential deepening of Russia ties and BRICS alignment. Similarly, US defense deepening with India signals to Russia and China that India’s loyalty cannot be taken for granted.

3. Avoiding Alienation from Global South

Formal exit from BRICS would be read in the Global South as India “choosing the West” over the Global South. This would alienate India from its traditional constituency of non-aligned countries, weaken India’s claim to G20 and UN representation, and marginalize India’s influence in climate negotiations and development finance forums.

India’s 2023 G20 presidency was predicated on claims of representing the Global South; exiting BRICS would undermine those claims.

4. Development Finance and Technical Cooperation

NDB, though limited, provides useful alternative development finance. India uses NDB for specific projects (Delhi-Ghaziabad-Meerut Regional Rapid Transit System opened October 2025 with NDB financing) and benefits from local-currency lending that reduces forex pressure. Similarly, BRICS technical cooperation on agriculture, health, disaster risk reduction offers limited but non-trivial benefits.

5. Domestic Political Rationale

Within India, maintaining BRICS membership allows the Modi government to appeal to nationalist constituencies that view Global South solidarity as morally imperative and BRICS as proof of India’s great-power status. Exit would trigger domestic criticism from opposition, media, and intellectuals claiming India surrendered to Western pressure.

Why Full Commitment Is Impossible

Yet these rationales do not translate into genuine strategic commitment. India cannot—and will not—fully integrate into BRICS for structural reasons:

China’s Centrality: India cannot commit to a bloc where its greatest threat is the dominant voice. This contradiction cannot be resolved through diplomacy or institutional redesign.

Democratic Values Contradiction: India cannot position itself as a values-based ally of the West (Quad, EU partnerships, democratic leadership claims) while simultaneously deepening military and political alignment with an authoritarian bloc.

Economic Dependence on West: India’s growth trajectory, technology acquisition, capital flows, and global trade all depend on Western integration. This is not a temporary dependency but a structural feature of India’s development model. India cannot sacrifice Western ties for BRICS solidarity without sacrificing growth.

Strategic Autonomy Doctrine: India’s entire foreign policy is predicated on “strategic autonomy”—the ability to make independent decisions without bloc alignment. Full BRICS commitment violates this doctrine by subordinating Indian interests to bloc positions.

India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar has stated: “The India Way, especially now, would be more of a shaper or decider rather than just be an abstainer.” This implies India will shape institutions rather than join coalitions. BRICS membership as full commitment contradicts this vision.

The Probable Trajectories—How India Will Disengage Without Exiting

Given the structural contradictions and the logic for staying, India’s likely trajectory over the next 5-10 years involves compartmentalization, not exit. Several scenarios are plausible:

Scenario 1: “Instrumental Membership” (BASELINE—60% Probability)

India remains formally within BRICS but downgrades real commitment:

- Attends annual summits; sends high-level representation but without substantive engagement

- Uses BRICS chair (2026) to redefine bloc toward development/economics and away from military

- Selectively participates in NDB financing for specific projects; does not build long-term developmental reliance

- Declines military exercises and security cooperation

- Maintains bilateral relations with individual BRICS members (Russia, Brazil) but on bilateral terms, not as BRICS coalition

- Invests strategic energy elsewhere (Quad, US partnership, minilaterals)

Outcome: BRICS becomes a “talking shop” for India—a forum for diplomatic rhetoric but not strategic alignment.

Scenario 2: “Silent Exit” (MODERATE—25% Probability)

India does not formally withdraw but progressively margininalizes itself:

- Representation at BRICS forums drops to technical/junior levels

- India misses exercises, provides perfunctory responses to joint statements, avoids new commitment-intensive initiatives

- 5-7 years of gradual devaluation until BRICS membership is nominal only

- Resembles US relationship with UN in some periods: formal member but minimally engaged

Outcome: BRICS becomes a China-Russia platform with India as a ghost member.

Scenario 3: “Dual-Track India” (EMERGING—20% Probability, Could Increase)

Most sophisticated scenario: India maintains formal BRICS participation but builds parallel, denser architectures:

- Deepens Quad (potentially expanded to include South Korea, Vietnam, Philippines)

- Strengthens I2U2 (India-Israel-US-UAE) and variants

- Pursues minilaterals with France, Japan, Australia, EU states

- Negotiates bilateral FTAs with US, EU, UK (already underway)

- Hosts Indian Ocean littoral forums and ASEAN-centric institutions where India leads rather than participates

Outcome: BRICS becomes peripheral to India’s strategic architecture while India maintains nominal membership for hedging purposes.

Scenario 4: “Shock Exit” (LOW—10% Probability, Could Increase if Triggered)

Formal withdrawal triggered by:

- BRICS-level declaration backing China on Taiwan or LAC

- BRICS military pact that formalized anti-US alliance structure

- Domestic political shift in India toward explicit Western alignment (unlikely under Modi but possible under future government)

- Sustained Chinese military aggression (e.g., major LAC escalation) that forces India to choose

Outcome: Formal exit; India joins Western institutions (NATO partnership, closer NATO-India institutional ties, etc.).

The Bangladesh Factor—South Asia’s Geopolitical Realignment

An important contextual factor: India’s regional position in South Asia has degraded significantly, with cascading implications for BRICS strategy.

Bangladesh’s Pivot (August 2024 onward):

The fall of Sheikh Hasina’s pro-India government in August 2024 and the rise of Muhammad Yunus’ interim government has fundamentally reordered South Asian geopolitics. Bangladesh is deliberately reducing Indian dependence:

- Pakistani Outreach: Meeting between Yunus and Pakistan PM in December 2024; agreement to improve bilateral relations; military cooperation expansion; joint maritime exercises (Bangladesh-Pakistan-China AMAN25 drills, February 2025)

- Chinese Alignment: Bangladesh exploring defense production facilities with Turkey (positioning Bangladesh as hub for Turkish arms in South Asia); Chinese investment in Lalmonirhat airfield near India’s Siliguri Corridor

- Reduced India Reliance: Bangladesh explicitly pursuing “India-free foreign policy”

India’s Strategic Problem:

By 2024, India had positioned Bangladesh as a success story—proof that India’s “neighborhood first” policy worked. Bangladesh had been India’s closest South Asian ally, a counterweight to Pakistan, a source of economic complementarity. The loss of Bangladesh represents not just a diplomatic setback but a fundamental erosion of India’s South Asian strategic architecture.

The BRICS Connection:

Bangladesh’s pivot to Pakistan and China signals a broader reordering in which India’s regional influence is declining precisely as China’s is rising. In this context, India’s BRICS participation becomes even less strategically valuable. BRICS does not help India manage South Asian challenges; it only deepens India’s integration with the very power (China) that is displacing India’s regional influence.

India’s 2026 BRICS Chair—A Repositioning Opportunity

India’s BRICS chair for 2026 provides a window to reshape the bloc’s trajectory. India’s outlined priorities—Resilience, Innovation, Cooperation, Sustainability—are deliberately development-focused and explicitly avoid security/military dimensions.

India’s Chair Strategy:

- Redefine BRICS Away from Military: Emphasize institutional, economic, and development cooperation; marginalize “Will for Peace 2026”-style military exercises

- Humanitarian and People-Centric Focus: Shift BRICS’ narrative from geopolitical competition to development equity, climate finance, and social inclusion

- Reform of Global Institutions: Position BRICS as force for reforming UN, IMF, WTO rather than replacing them; aligns with India’s preference for shaping existing institutions

- Minilateral Deep Dives: Use chair to launch specific development initiatives (agriculture, health, disaster risk reduction) that deliver tangible benefits without military implications

Likelihood: India’s chair presidency will reveal whether BRICS can be reformed away from military/security focus or whether China-Russia bloc will consolidate despite India’s efforts.

Strategic Autonomy in Practice

The question posed—”Why stay in BRICS when most of India’s interests are anti-BRICS?”—receives its answer through India’s actions rather than statements: India is not truly staying in BRICS; it is redefining its relationship to progressively minimize strategic commitment while preserving nominal membership.

This is strategic autonomy in its most sophisticated form: maintaining multiple options, extracting value from various alignments, but committing fully to none. India will not formally exit BRICS—the political, diplomatic, and reputational costs are too high. Instead, India will engineer a slow-motion downgrading, compartmentalizing BRICS into a narrow economic and development forum while investing strategic priority in partnerships (Quad, US bilateral, minilaterals with like-minded democracies) that align with India’s values, interests, and threat perception.

The Trajectory:

By 2030, India’s BRICS membership will likely resemble a formal arrangement without substantive content. India will attend summits, maintain nominal participation, and selectively use BRICS platforms for development finance. But the strategic architecture that India prioritizes will have shifted decisively toward the Quad, deepened US partnership, minilateral coordination with EU and like-minded powers, and bilateral engagement with individual countries.

The Structural Inevitability:

India cannot remain a full BRICS partner because BRICS is becoming what India explicitly does not want to be: an anti-Western military alliance. India’s core interests—China deterrence, development partnership with Western countries, technological integration with the US and Japan, democratic self-conception—all push India toward the West, not away from it.

The 2026 naval exercise opt-out was not a one-off decision; it was a marker of a longer process. India is signaling that it has set limits on how far it will go in militarizing its BRICS commitment. Those limits will become increasingly constraining as BRICS deepens its anti-Western alignment. Eventually—through India’s 2026 chair strategy, its increasing investment in Quad and minilateral partnerships, and its declining participation in BRICS security initiatives—BRICS will become peripheral to India’s strategic architecture.

India’s strategic autonomy doctrine ultimately points not toward BRICS but away from it. The next decade will involve India managing that transition diplomatically.